On Jake Brewer

Ten years after we lost my friend Jake Brewer, his loss echoes large, but the his legacy is even larger.

Ten years.

Ten years ago, on September 19, 2015, we lost my friend Jake Brewer.

It was, to put it mildly, a shock. And a loss that echoes even to this day.

Jake was a connector. But that phrase doesn’t really do him justice. He was more accurately a hub and spoke for people. Just as people and airplanes need to connect through central hubs to transit to the final destination, Jake was the central hub through which so many people, connections, and friendships flowed. Jake would meet someone new, they’d tell him about something they were working on or someplace they were going, he would make an instant connection in his mind, then say “You should really meet my friend so and so…” Jake would then route you to the person. I just looked in my gmail and found a bunch of old emails from Jake connecting me to people, some of whom are still friends to this day. He was like a human “People You Should Know” algorithm.

I say this with the respect of someone who is also a very good human connector, more so then than I am now, and that when you’re good at something it can be annoying, humbling, and maddening to stand next to someone who is that much better at it than you.

Jake and I were good friends. Few people I have ever known possessed the same natural impulse to connect people with the understanding that it had to be followed with intentional work to maintain them. But he was so good at it that sometimes it felt like I was a rec league softball player standing next to an MLB player. Or if we’re being more generous to myself, the way a good sprinter might look at a decathlete and be like how the fuck do you do all of that, at once, so well? But it was never in a way that left you that mad at Jake, or at least not for very long.

Jake understood that the connections were only beginning, that community came from shared experiences, reaching out, and showing up. These are all things that stretched him thin at times but also made him a great friend.

A few weeks before Jake died, the stars aligned despite his White House job and his two-year-old and everything else in his life and he was able to come join for a birthday weekend away at a house I rented.

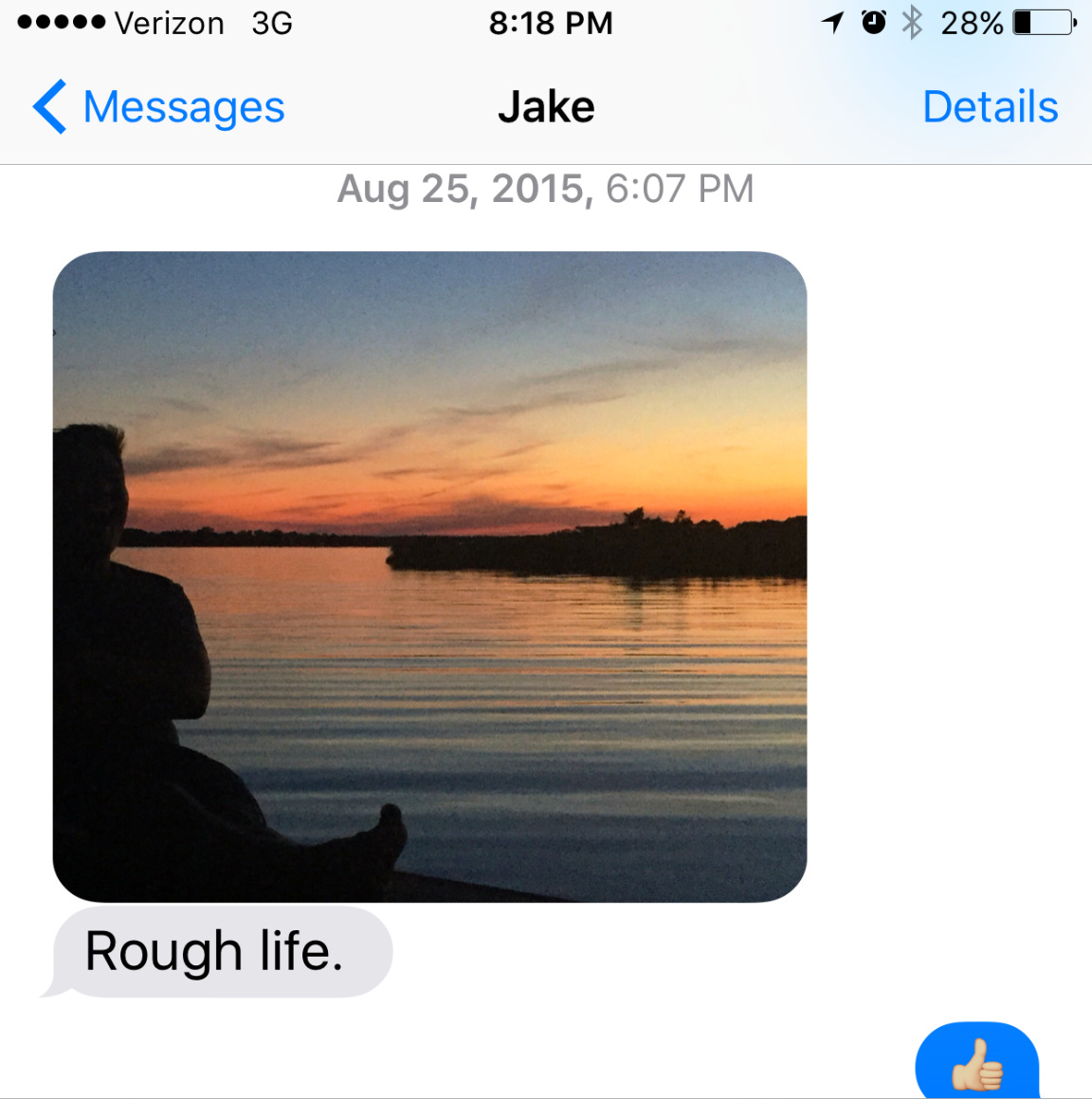

We sat on a dock staring out at the Chesapeake Bay listening to Otis Redding on a bluetooth speaker (yes in retrospect the song choice seems a little on the nose given its history). We talked about getting older, about the future, about dreams, and he let it slip that he was going to be a father again. It was what we needed, what we loved, about spending time with each other. This is the last photo he ever sent me.

When Jake and I would talk about human networks, and recall this was at the dawn of the social networking era, it was with an inherent understanding of their nature and power.

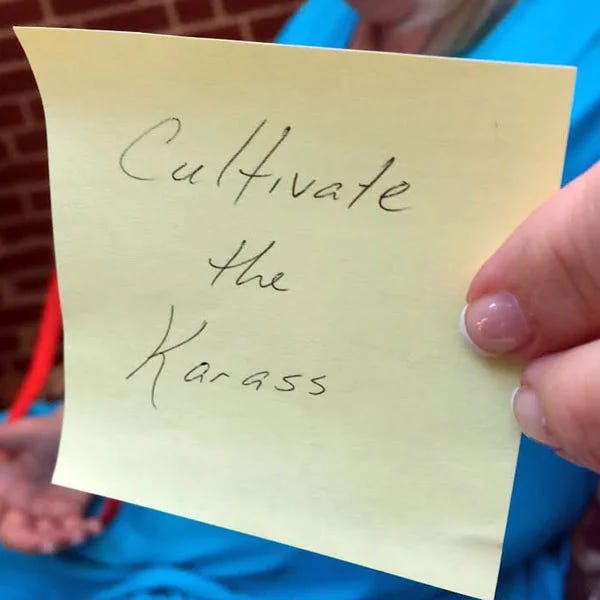

Jake’s belief in connections, community, and networks led to the legend of the sticky note that was discovered at his desk at the White House after he died that said, “Cultivate the Karass,” the karass being a phrase from Vonnegut’s “Cat’s Cradle” to describe “a team that do God’s Will without ever discovering what they are doing.”

Jake Brewer cultivated a hell of a karass.

We held his funeral at the National Cathedral, in the space usually reserved for Presidents or Senators. I had the honor of being an usher at that funeral. For whatever reason, I stuck my phone in my pocket and recorded a video as we walked out at the end. It shows endless rows of pews packed with standing mourners. The National Cathedral is full. We were all part of the karass that Jake had built.

Now that it has been ten years, and a rollercoaster decade, it's tempting to try to imagine how my friend might have felt about the future he never saw. But I don’t want to extrapolate to guess how he might have handled these unprecedented political times. All I can say for sure is that I am sad that I do not have his friendship, wisdom, and counsel to navigate the last ten years.

But I don’t need to imagine what the lessons are that I learned from Jake that I still carry with me.

That you should introduce and make the connection between people who might not know each other but should.

That you should always Rock Band or karaoke with your friends when you can.

That it is your duty to pull together the dinner at the conference for your friends you have and the ones you make there.

That you should probably not send your friend to run a campaign office in western North Carolina and then bail on them to go to Pennsylvania instead (he was fine, he had a blast, I think they wanted to elect him mayor by the end).

That renting a houseboat because it was the easiest way to travel to and have housing at a waterfront wedding is absolutely a good idea.

That you should not call the groom on their wedding day lost from said houseboat to ask for him to stand on the lawn of the wedding venue and wave his arms so you can find it from the water.

That you should go to the birthday weekends for your friends even if it's complicated because you never know when it may be your last chance.

That you should hope to live a life so full that your funeral fills the National Cathedral.

That your karass should be so big that your friends have to find a place to hold your wake that can hold at least 500 people on short notice.

That your legacy should inspire Substack posts a decade later.

Jake, my friend even though it has been ten years, you are not forgotten. I love you and miss you brother.

And finally, a note on grief.

When Jake died, it was obviously a severe shock to everyone who knew and loved him, there’s no shock more severe to a hub and spoke network than the loss of a hub. But it was also the first time a lot of us had lost someone who wasn’t a family member but a peer.

I learned a lot about grief over that period. Not just from experiencing it, as I obviously did from the loss of my friend, but from watching how others dealt with it. Especially when people interacted with Jake’s wife Mary Katharine Ham.

One thing I have never forgotten was watching how people would arrive at the house for the first time and they would greet MK, Jake’s pregnant widow, and for lack of a better term, would dump their feelings about the loss on her. These people were not being malicious, they just had raw emotions, and it made sense to them to share them with the person closest to Jake. But like then they maybe felt better but now she was getting that from like…hundreds of people over and over again (see aforementioned full funeral at the National Cathedral).

Now MK is maybe one of the strongest people I have ever met and thankfully also an extrovert so I think she was probably okay with it but it did make me really recognize how unprepared most of us are to deal with grief.

MK had been involved with the Travis Manion Foundation, a wonderful foundation for veterans honoring the legacy of Marine 1stLt Travis Manion. So she had friends there who had also received the worst news of their lives, who had gone through that loss and rebuilding, and were so steadying in that moment. There’s been a lot written about the civilian-military divide but I recall thinking at that moment there was a part of America that had experienced how to deal with this kind of young loss, and a part that never had to before, and those two worlds were meeting when they usually don’t.

Over the years MK has written about the last day, talked about grief on podcasts, and provided what I think is one of the best guides on how to help someone grieving (or going through a crisis). MK I’m thinking of and sending love to you and your family today too.

Incredibly touching, Adam. Jake is missed greatly.

❤️